The oxidation of elemental sulfur (S⁰) to sulfate sulfur (SO₄) in soil is a biological process and is carried out by several kinds of microorganisms. The rate at which this conversion takes place is determined by three main factors:

-

the microbiological population of the soil;

-

the physical properties of the S⁰ source; and

-

the environmental conditions in the soil.

Microbiological population in the soil

Most agricultural soils contain some microorganisms that can oxidize S⁰. However, the most important organisms in this respect are a group of bacteria belonging to the genus Thiobacillus. It’s the number of these bacteria that generally determines the degree to which S⁰ is converted to SO₄ in soils, and there can be large differences between soils in the population density of Thiobacillus. Under laboratory conditions, researchers can markedly increase the rate of S⁰ oxidation in some soils by inoculation with Thiobacillus. However, under field conditions, inoculation has not been found very effective.

When a source of S⁰ is added to a soil, it generally stimulates the growth of S-oxidizing bacteria, and the population of these organisms increases.

Physical properties of the S⁰ source

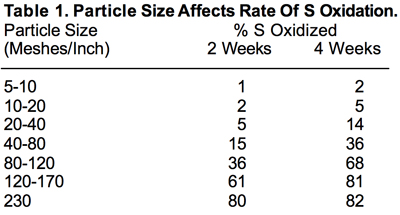

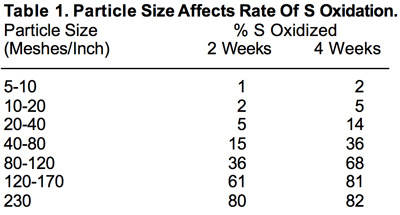

The physical property that has by far the greatest effect on the rate of S⁰ oxidation is particle size. The finer the particle size, the larger the surface area exposed to soil microorganisms and the more rapid the oxidation process. Table 1 clearly shows this effect of particle size.

A mesh of 5 to 15 is roughly the size range of blended fertilizers — sizes so large that S particles in that range oxidize to SO₄ very slowly. For S⁰ to oxidize to the plant-available SO₄ form at even moderate rates, it must be of a very fine particle size. But finely divided S is very difficult to handle, in addition to posing a fire hazard under some conditions. These obstacles would seem to largely rule out S⁰ as a fertilizer material. However, fertilizer manufacturers have developed techniques to improve S⁰’s handling characteristics and agronomic effectiveness. First they grind S⁰ to a very small particle size range and then agglomerate it to a size compatible with granular fertilizer materials. About 10 to 15 percent of expandable clay is added during the agglomeration process. The resulting material is more easily handled than finely divided S. In theory, when such a particle is applied to a soil, it comes in contact with soil moisture. As this moisture is absorbed by the particle, the clay expands, which in effect breaks the particle down into a much finer size range. The rate of oxidation to SO₄ increases accordingly. When discussing S⁰ fertilizers from here forward, it’s assumed the particles has been manufactured to break down rapidly on contact with soil moisture.

Environmental conditions in the soil

Since the oxidation of S⁰ to SO₄ is a biological process, conditions must favor growth of the organisms in order for oxidation to proceed at optimum rates. The following environmental conditions have proved influential on the rate of S⁰ oxidation:

· Temperature

· Soil moisture and aeration

· Soil pH

· Fertility status of the soil

Temperature

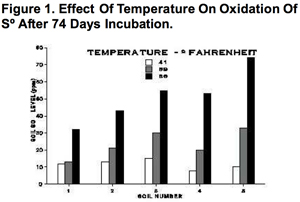

Like most biological processes, So oxidation decreases at both low and high temperatures. Most studies have shown relatively low rates of oxidation below 55 to 60⁰F, and steady increases in oxidation rates up to 100⁰F. At temperatures above 130 to 140⁰F, oxidizing bacteria die. All things considered, the optimum temperature range for oxidation is 75 to 105⁰F. Figure 1 shows the marked effect of temperature on oxidation rates of S⁰.

Soil moisture and aeration

Most S⁰-oxidizing bacteria require oxygen: Any condition that restricts the oxygen supply in a soil will reduce the activity of S⁰-oxidizing bacteria. Oxidation of S⁰ is most efficient at moisture levels close to field moisture capacity. Both waterlogging and excessively dry conditions greatly reduce the rate of S⁰ oxidation.

Soil pH.

Most Thiobacillus organisms thrive best under acid soil conditions. When a fertilizer source of S⁰ is applied to a soil, oxidation occurs most rapidly under acid conditions.

Fertility status of the soil

Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria require most — if not all — of the nutrients required by plants. It’s not surprising, therefore, that oxidation of S⁰ proceeds more rapidly in fertile soils. The bacteria and plant roots compete for nutrients, causing temporary nitrogen (N) deficiencies in plants under high S⁰ oxidation rates. Thiobacillus requires ammonium rather than nitrate N. High soil nitrate levels can be toxic to the bacteria.

What does all this mean for using these two forms of Soin fertility programs? Since all S absorbed by plants is in the SO₄ form, SO₄ fertilizer sources are immediately available for plant uptake. And since all S⁰ sources must undergo conversion to SO₄ in the soil, a certain time lag occurs between application and absorption through the root system. Any soil or climatic condition that suppresses the oxidation process will, obviously, extend the time lag. For this reason, when differences are observed between the effectiveness of these two chemical forms of S, the SO₄ forms usually outperform S⁰ forms. The trials with wheat in Arkansas mentioned previously are a case in point. Table 2 compares the effectiveness of SO₄ over S⁰ at various application rates in these trials.

Treatments were applied to wheat exhibiting S deficiency symptoms in the Spring (May), and plant analysis samples were collected three weeks later. Judging by the S levels in plant tissue, three weeks was clearly not enough time for S⁰ oxidation under the existing conditions.