Sulfur’s Role in Converting Nitrogen to Protein

Sulfur is essential for synthesizing nitrogen containing amino acids such as methionine, cystine and linking together multiple cysteine molecules, the structural constituents to build proteins8. Nitrate reductase, a key enzyme that directly impacts the utilization of nitrate in protein biosynthesis (Fig. 1), shows reduced activity when sulfur is limiting6,9. As early as the 1930s, it was reported that sulfur-deficient plants were unable to effectively utilize nitrate for protein synthesis. Under such conditions, nitrate accumulates in the leaves due to the diminished activity of nitrate reductase. Those findings help explain why sulfur-deficient plants typically accumulate high levels of nitrate, amines, and amino acids (collectively referred to as non-protein nitrogenous compounds) while containing lower amounts of protein.

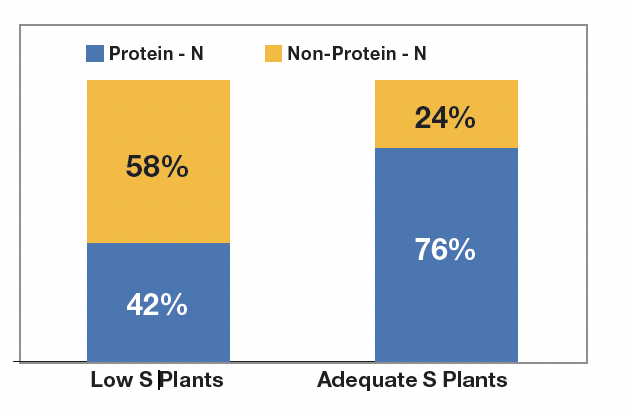

The implication is that when the protein of plants grown under low sulfur conditions is compared to similar plants grown with adequate sulfur, the two types of plants do not contain the same amount of protein. In sulfur-sufficient plants, a majority of the nitrogen is present as protein, while in sulfur-deficient plants, non-protein nitrogenous compounds (such as nitrate and amino acids) predominate (Fig. 2)9.

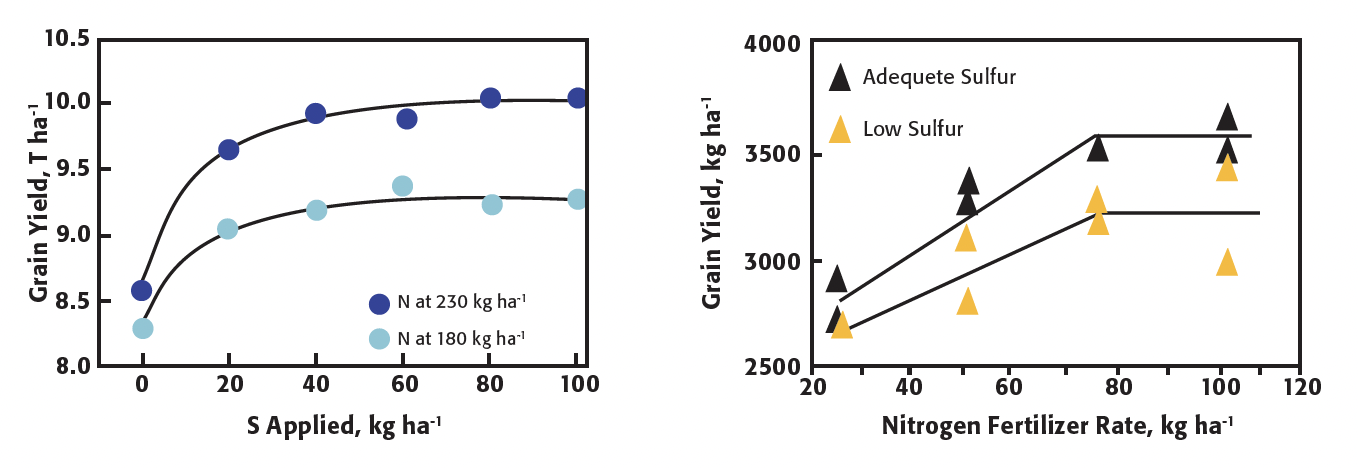

These findings indicate that crops grown on soils which cannot supply adequate S will have an impaired ability to convert N into protein and therefore decreased NUE. Consistent with these observations, field experiments have demonstrated that adequate S nutrition is required for better root N uptake and NUE in plants (Fig. 3)10,11.

Salvagiotti et al. (2008) further demonstrated that grain production per unit of applied N fertilizer was about 50% higher in S-sufficient plants compared to those grown under low S supply11.

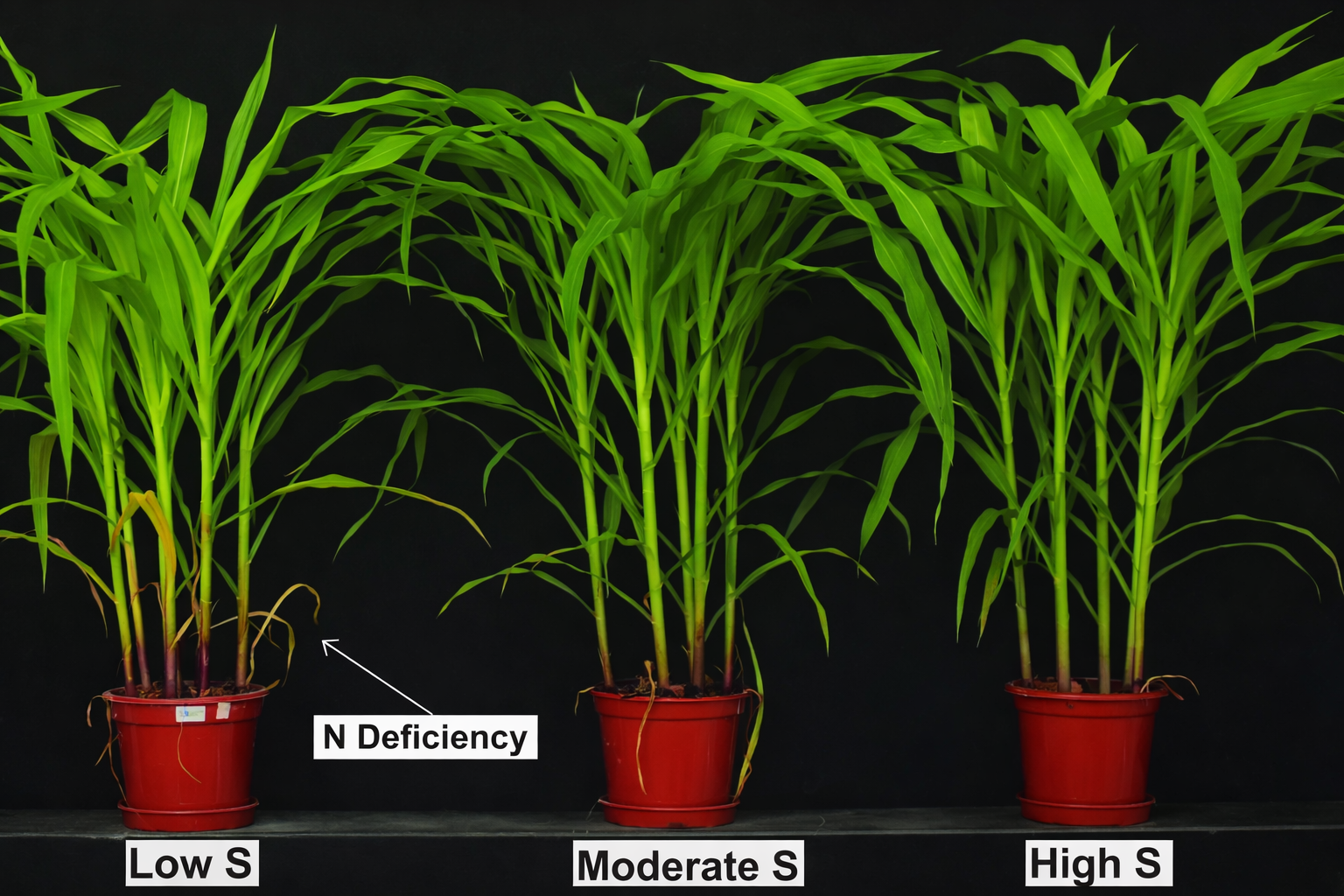

Figure 4: Even when nitrogen is supplied at a sufficient rate, plants that lack sulfur can show N deficiencies compared to plants that have adequate or high S supplied to the soil7.

Conclusion

Evidence continues to support the role that proper sulfur nutrition has in enabling crops to improve NUE. Sulfur is known to be a critical mineral nutrient necessary for the proper function and activity of nitrate reductase, a key enzyme involved in converting nitrate into proteins. Consequently, S-deficient plants accumulate high amounts of unused nitrate, which then reduces the capacity of plants to utilize N from the soil. If nitrogen is not effectively incorporated into protein biosynthesis, plants lose their ability to take up N, even with sufficient N fertilization.

References:

- Waqas, M., Hawkesford, M. J. and C. M. Geilfus. 2023. Feeding the world sustainably: Efficient nitrogen use. Trends in Plant Science 28.5: 505-508.

- Grandy, A. S, et al. 2022. The nitrogen gap in soil health concepts and fertility measurements. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 175: 108856.

- Baojing, G. et al. 2023. Cost-effective mitigation of nitrogen pollution from global croplands. Nature 613.7942: 77-84.

- Imsande, J., and B. Touraine. 1994. N demand and the regulation of nitrate uptake. Plant Physiology 105.1: 3.

- Prosser, I. M., et al. 2001. Rapid disruption of nitrogen metabolism and nitrate transport in spinach plants deprived of sulphate. Journal of Experimental Botany 52.354: 113-121.

- Cakmak, I. 2025. Illustration of Root Nitrate (NO3–) Uptake and Assimilation. Adapted from Imsande & Touraine, 1994. Personal communication. Sabanci University.

- Cakmak, I. et al., 2025. Unpublished data, Sabanci University.

- Zenda, T. et al. 2021. Revisiting Sulphur-The Once Neglected Nutrient: It’s Roles in Plant Growth, Metabolism, Stress Tolerance and Crop Production. Agriculture 11, 626.

- Zhao, F. J., et al. 2006. Effects of sulphur on yield and malting quality of barley. Journal of Cereal Science 43.3: 369-377.

- Rendig, V. V., C. Oputa, and E. A. McComb. 1976. Effects of sulfur deficiency on non-protein nitrogen, soluble sugars, and N/S ratios in young corn (Zea mays L.) plants. Plant and Soil 44: 423-437.

- Salvagiotti, F., et al. 2008. Nitrogen uptake, fixation and response to fertilizer N in soybeans: A review. Field Crops Research 108.1: 1-13.